Ricardo Montagner, the small farmer fighting for a major transformation in the country’s energy model

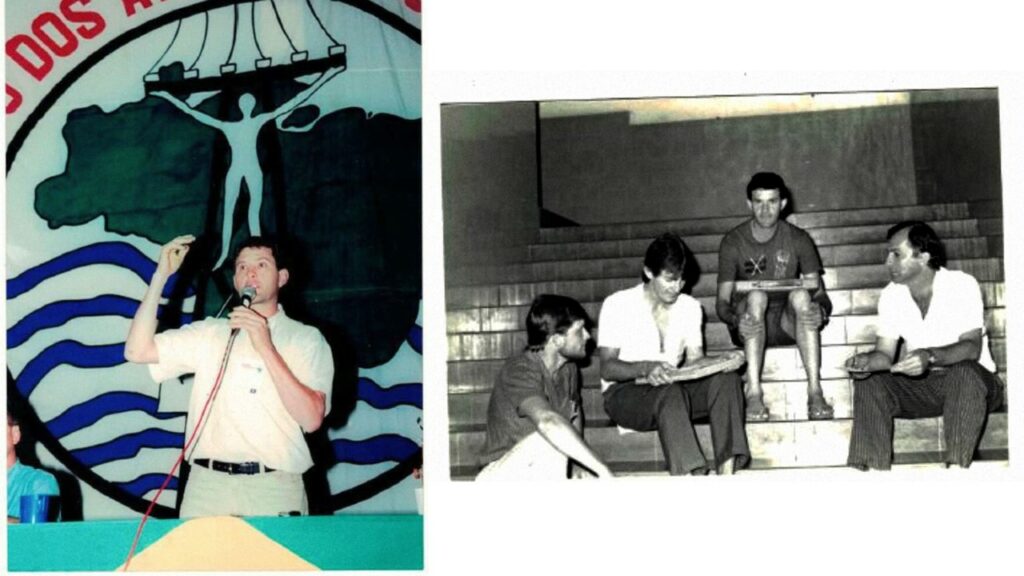

The coordinator, who saw the Movement of People Affected by Dams born in the Uruguay River Basin, engaged in great struggles throughout Brazil and talks about its enchantment with the plurality of the organization with respect to different local realities

Publicado 09/09/2021 - Atualizado 09/09/2021

From the small municipality of Charrua, in the limits of subtropical Brazil, Ricardo Montagner fights for a future where there are no borders for social justice. “As a militant, our role is to act in the construction of the fight for human rights, so that they exist for people from all corners of this country and of this world because human beings need to have a dignified life, they need to have, in fact, a model of sustainable development, not a model that is destructive, that leads to the death of people, that destroys the places and the lives of residents”. For the MAB coordinator, the local struggle against a dam that would change the direction of the waters and the lives of the residents of the Uruguay River Basin, 35 years ago, was an awakening to class consciousness.

“The first fight was for the defense of our land, our survival, in defense of our community, a place where we are still living and planting , but then we understood that the fight was bigger,” he says.

The fight in the Uruguay River Basin

At the time when Ricardo had the first contact with the movement that would become the MAB, he was one of 200,000 people threatened by a project to build twenty-five hydroelectric dams in the Uruguay River Basin. “This was the context in which the Regional Commission of People Affected by Dams (CRAB) of the Uruguay River Basin emerged. At the time, we raised the flag Terra yes, Barragem no! ‘ which would become one of the great chants of the MAB, “he says. The resistance ensured changes in the hydroelectric project that preserved the lands where Ricardo was born, grew up, raised two daughters, and lives today with his wife Jane Granja producing food such as milk, vegetables, corn, and soybeans.

With this change in the project of the Machadinho Power Plant (which was possible after many struggles), the number of families affected by the work was reduced from 6,000 to 1,700, decreasing only 100 MW in the production of the hydroelectric plant. The victory in this struggle instigated in Richard the desire to follow militant so that more people could have their rights protected. He wanted the residents who were removed from their lands to be compensated precisely and to resettle the landless workers because there were examples of other works in the south of the country in which the affected ones did not have their rights repaired.

Before the construction of Machadinho, the construction of the Passo Real Hydroelectric Plant, on the Jacuí River (RS), had left thousands of people homeless and without their rights repaired. “And it’s not just the economic issue of compensation that matters, is it? But also the right of people to live there their bonds of friendship, cultural ties, traditions, all this had been broken”, comments Ricardo.

The coordinator explains that these projects of the large hydroelectric power plants of the 1980s still followed a model created by the military dictatorship, which did not take into account the social issues surrounding them. “The idea was to flood the land and drive people out. Flood the area, flood the communities, the cemetery, the church, the football field, without repairing the damage, without talking to the communities, without relocating people. So we understood that it was necessary to fight to prevent these works from changing the fate of more people. We decided to build a broader struggle at the national level, “recalls the militant.

A national articulation to change the energy production model

Ricardo explains that the union with other affected people showed that it was necessary to change not only the reality of the Uruguay River Basin but the model of energy production and distribution throughout Brazil. “We realized that we needed a more rational, more sustainable, and fairer model for everyone.”

The coordinator recalls that, at the time when the MAB was organized as a national movement, there was a great effervescence of popular struggles. “Then at that time, we lived a great advance, through the basic ecclesial communities, especially in the countryside, when the Landless Movement, the most combative unions, and the progressive movements of the church were born. All these movements played an important role in the construction of a new society that sought to fight for the right of the oppressed, against these large projects linked to the interests of national and international capital, “he says.

This national articulation that began to be built along with other movements of the countryside connected the affected of the Uruguay River, on the southern borders, to those of Itaparica and Sobradinho, on the São Francisco River, and also to Altamira and Balbina, in the middle of the Amazon rainforest and many other localities. It was these junctions of the struggles that gave rise to the MAB as a national movement that in 2021 turned 30 years.

“I see this as a great virtue of MAB, right? This ability to articulate the debate with this plurality that exists within a social movement, respecting the regional differences of the territories, the realities of each biome, the question of gender, the question of local culture, always seeking to create and organize the struggle in the breadth”, emphasizes Ricardo.

“We hope that this will be repeated for another 30 years, in a new moment with great advances and overcoming the challenges that we live in now. Together we will achieve great cultural advances, great advances in knowledge, solidarity, and struggle, “concludes the activist.

* This article is part of a series of profiles of MAB coordinators produced in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Movement.