Profit by any means: understanding why the electrical sector establishes high tariffs for the population

The electricity industry of Brazil is dominated by large international corporations that obtain extraordinary profits at the expense of Brazilian natural resources and the pockets of the working class

Publicado 05/10/2020 - Actualizado 31/10/2025

Electrical power impacts peoples’ lives directly. It represents a fundamental input stemming from all the productive chains, but above all, it is a fundamental right for people. Brazil has natural resources with a high yield through hydroelectric generation (62% of the energetic matrix of the country comes from this source). Nonetheless, the low cost of production is not used to guarantee electrical power at affordable prices for people; instead, it is the contrary.

The logic that dominates the market is far conceiving energy as a right. Reality shows that the country’s electrical industry is a great business that produces extraordinary profits for large international corporations and their shareholders.

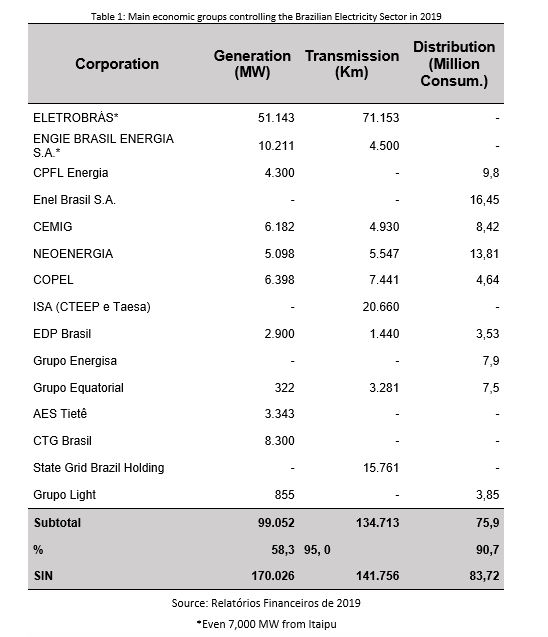

The owners of the electricity industry

According to a study published this May by the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB, after its acronym in Portuguese), fifteen economic groups monopolize the control over the electricity industry in Brazil. Among them, only three are state-owned and are also being privatized from the inside: Eletrobrás, which holds about 30% of the country’s installed power and 50% of the transmission system; Copel, which belongs to the government of Paraná; and CEMIG, a company controlled by the government of Minas Gerais, but which has only 17% of the state stock control.

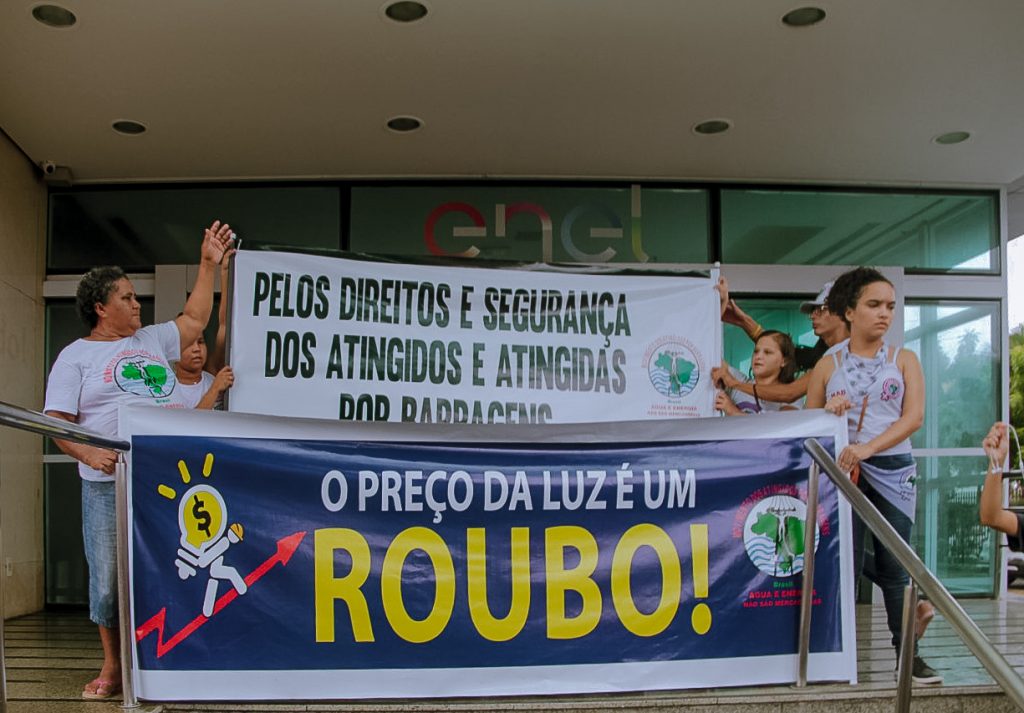

For Gilberto Cervinski, from the national coordination of the Movement of People Affected by Dams, electrical energy “is dominated by an international cartel of transnational companies which impose high priced electricity bills on people, control all the structures of the State, further privilege the already privileged class, and punish underpriviledged people, setting up a model that runs counter to the interests of the people and the country,” he says.

“Historically, we have denounced that the price of electrical power is a rip-off. Despite the low production cost, people pay one of the highest rates in the world. This is this model’s greatest contradiction. They charge people expensive prices and at the same time deliver extremely cheap energy to the richest, such as large industrial companies and shopping centers—the so-called ‘free consumers’,” explains Cervinski.

This results in excessive spending on electricity being reflected on the budget of the poorest in the population. According to the survey published in the Outras Palavras blog, based on data from ANEEL (National Electric Energy Agency) and IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), the average cost of the residential rate in the first six months of 2020 remained at R$ 135, which represents more than 10% of the monthly income per capita in the country in relation to the 2018 data.

Considering that a large part of the population has income equal to or less than the minimum wage, the impact power tariffs have on families’ pockets is huge.

Historical problem

“Our independence began with Portugal transferring an enormous debt to Brazil, the colony that was no longer a colony. We were born within this logic, and with electrical industry, it is the same: it was born in the Global North, the center of development of capitalist production and of the logic of increased productivity, arriving in Brazil with those great companies, used to publicize their equipment and create the market for the new industry,” explains Professor Dorival Gonçalves Junior, of the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), whose doctoral thesis was on Brazil’s electrical industry.

The electricity sector was totally centralized in the hands of foreign capital until the 1930s, he explains, and it was only during the great economic depression of 1929 that the first large investments in the generation of electricity by each state began.

In Brazil, companies were already selling energy at international prices and it was only at that time that the price began to relate to the cost of local production, leading to increased control over foreign companies, which subsequently began to divest.

Through twists and turns, a state electricity industry began to emerge within the framework of the first effort to build Brazil as a sovereign nation, more than 100 years after the “Grito de independência”. After the end of the Second World War, electricity was consolidated as a sector dominated almost entirely by the State.

According to Dorival, the current phase began in the 70s, when the first experience of destabilization of the electricity industry was carried out by the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile. This dictatorship began after the coup that led to the death of the socialist president Salvador Allende in 1973. That phase, he explains, “is founded on the principle that this activity should be carried out by private initiative establishing a horizontal industrial structure in four business sectors: generation, transmission, distribution and commercialization. In the present, this vision constitutes the global hegemony,” he points out.

The transference

In Brazil, the industry returned to the hands of private initiatives in the 90s, during the government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. At the time, Dorival explains: “Those enormous assets, which had been organized by the State and built through the people’s efforts, were launched into the hands of the market. At the same time, and to attract international investors, the price of electricity was internationalized again. So, from that moment on we enter into the contradiction of having the conditions to produce very cheap energy, while at the same time have high tariffs. The industry has become a great and highly coveted business as it generates extraordinary profits.” But, he says, “That didn’t just start now; even with alternations or modifications, the main concern was almost always the financial system.”

The electrical industry requires constant investment of capital, construction of plants, purchase of materials, generators, transmission lines, etc. In privatizations, all these costs are transferred to the consumer, even having been amortized over several years. In other words: private capital was handed a sector that the State had built and society had paid for, so from now, everything would be profitable for companies. For Dorival, “that is a solution that capital always had at hand, and which never left the scene.” That is why they are so reluctant for states to assume control; that business is a gold mine for them.”

Without control

The Partido dos Trabalhadores’ (PT) arrival to the government generated some advances, but the model remained under the control of private capital and the international market. Even without structural changes, the reform of the sector in 2004, during the first Lula administration, emphasized the role of the State in planning, thereby withdrawing Eletrobrás from the privatization program.

In 2013, seeing that the industry was greatly increasing the costs of electricity, Dilma Rousseff’s administration exercised political action to try to control prices. She removed from the tariffs the costs related to amortization of the initial investment for construction of the plants and transmission lines.

Companies could only transfer the value of the operation’s cost, and this measure managed to reduce the price of electricity. Without political intervention on the part of the State, companies continue to eternally transfer that value into tariffs for the population.

“The electricity industry played a fundamental role in the coup against Dilma Rousseff,” says Dorival.”

Dorival points out that: “In the crisis of 2018, what was seen around the world was the difficulty of resuming growth. So, the capitalists will be wherever there are opportunities to profit easily. That is why they do not want anyone to have control of those assets, and every time there is a project in which the State tries to gain over them, the coups come.”

Sell the left-overs

Since the re-democratization, the idea of privatizing Eletrobrás has been floated around Brazil. Fernando Henrique Cardoso broke the states’ monopoly and placed Eletrobrás in the privatization program, just as Michel Temer had also tried to do, and failed. Bolsonaro’s neo-fascist government and his economic team, led by the ultra-neoliberal Paulo Guedes, are no exception; they are trying to advance the privatization of the company.

For the Movement of People Affected by Dams, “privatization destroys sovereignty, increases the cost of energy for the people, leads small and medium-sized companies into bankruptcy, prevents the recovery of the economy and generates mass unemployment. It only worsens the situation of the people and the country.”

And Dorival proposes the following reflection: “Imagine the effort to organize workers to build a company like Eletrobrás, with that same capacity, with that same structure. The State did that. And are you going to leave it to the market? The Global North have never allowed the market take over their power sectors. That is incredible.”

Translation: Ciro Casique Silva

Translation revision: Selene Rivas